Zimbabwe Country Profile

Zimbabwe

17 Million

Purpose and intended audience

Landscaping of existing Digital TB Technology tools and new relevant products that may be applied across the TB Care Cascade Model, and providing insight to product developers and partners into country-specific policy, regulatory and implementation processes.

Key numbers

Country TB profile

TB Cases the Health System is Identifying:

0.71 %

Health System Efficiency Ranking:

155

Business

Ease of Doing Business Ranking:

155

Economy

Income Category:

LOW INCOME

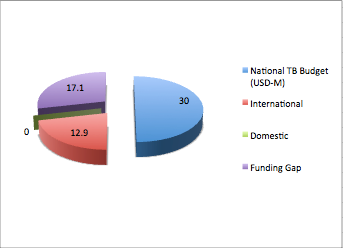

Budget & Financing

National digital TB landscape

Table 1: Digital TB Care Technology Tools currently in use

| PRODUCT CATEGORY | DEVELOPER | USAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostocs & Transport | ||

| QUAN TB | MSH-SYAPS (open source) | electronic quantification and early warning system for supply planning for TB treatment. |

| Early Care Seeking | ||

| VULA | Flow Interactive – Delloite Digital | Patient referral App |

| DYNA-VISION | Tech-Medic International | Patient tele-monitoring system |

| INYASHA | SolidarMed | Comms Software-connecting clients & health care providers |

| Patient Support & Direct Benefits | ||

| Clinical Mentoring Tool App | I-TECH | Operations and management of clinical mentoring in a decentralizing health care service provisioning |

| KUTENDEKA | SolidarMed | Software for enhancing operational processes within the healthcare providers value chain |

| ICT, Dashboard & AI | ||

| SAP [systems, applications & products | Health Management App | |

| TrainSMART | I-TECH [open source] | web-based training data collection system |

| Real-Time Monitoring | UNICEF | Data collection and Information Management Platfor for Malnutrition in Children |

| DHIS-2 | Open Source | Electronic Health Records |

| HIS - Health Information System | RTI-International | collection and analysis of routine health services data and non-routine data such as population estimates. |

| Vaccination | ||

| New Drug Regiment | ||

| Triage | ||

| Sequencing | ||

| Adherence | ||

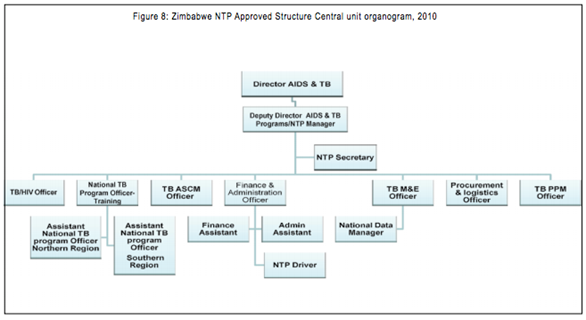

National TB country team

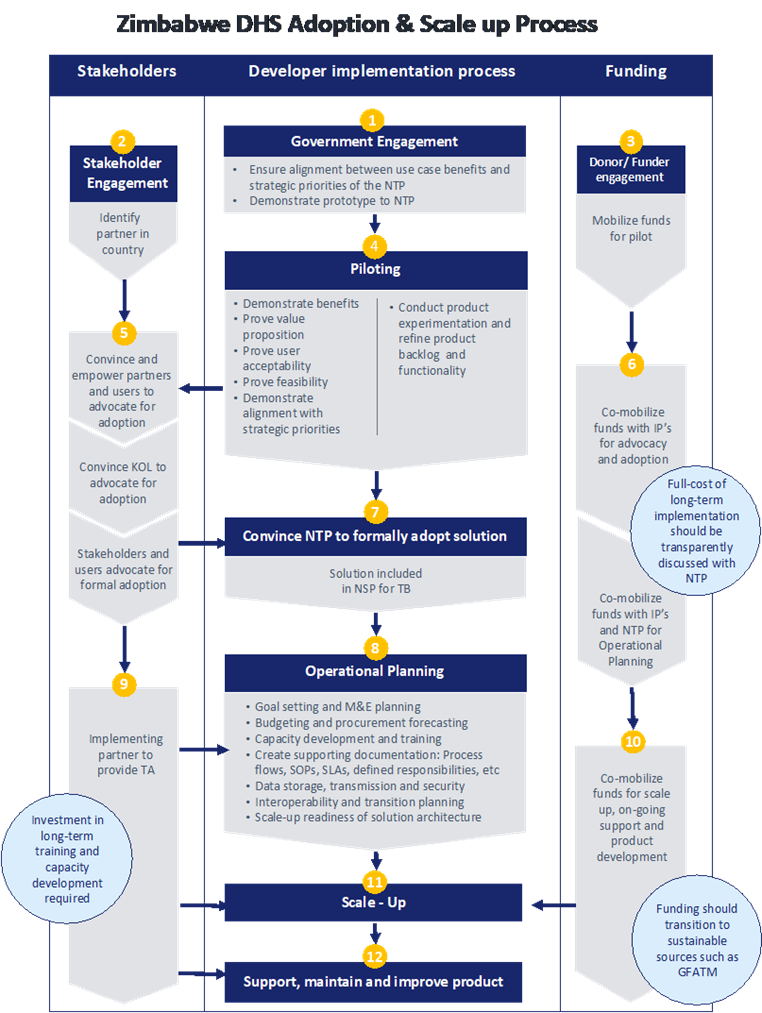

Market Entry Diagram

e-Health Policy & Regulation

Zimbabwe’s health service delivery is established at four levels: primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary. The Primary Health Care (PHC) is the main vehicle through which health care programs are implemented in the country. The main components of the PHC include maternal and child health services; health education; nutrition education and food production; expanded program on immunization; communicable diseases control; water and sanitation; essential drugs program; and the provision of basic and essential preventive and curative services.

The majority of health services in Zimbabwe are provided by the public sector (Ministries of Health and Child Welfare and Local Government, and to a lesser extent through Ministries of Education, Defense, Home Affairs and Prison services), both in rural and urban areas.

Public sector health services are complemented by the private sector, which includes both private for profit (e.g. industrial clinics, private hospitals, maternity homes and general practitioners) and not-for-profit private sector (e.g. mission clinics and hospitals and Non-Governmental Organizations) health facilities. The country is making efforts to increase collaboration and health service provision through numerous public private partnership initiatives.

According to the National Health Strategy there are gaps in the six pillars of health systems for efficient health delivery services:

- Public sector Human Resources (very high vacancy levels);

- High attrition rates of experienced health service and program managers.

- Access to essential drugs and supplies had been greatly reduced with stock availability ranging between 29% and 58% for vital items and 22% and 36% for all categories of items on the essential drugs list;

- Medical equipment, critical for diagnosis and treatment is old, obsolete and non-functional

- As a result of serious shortage and disruption of transport and telecommunications several programs including patient transfer, immunizations, malaria indoor residual spraying, drug distribution, supervision of districts and rural health centers have been compromised.

- The health system is grossly under-funded

e-Health Readiness in Zimbabwe:

e-Health Strategy Developed (https://www.who.int/goe/policies/countries/zwe_ehealth.pdf)

National Infrastructure

Internet and Communications Technology:

According to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) by Dec 2011, Zimbabwe had about 1.4million (12% of the population) accessing the Internet. The country continues to increase its access into the World Wide Web through numerous fiber optic links, such as the SEACOMM cable in the Indian Ocean. The mobile phone communications rate was estimated at 78.5% by the Postal and

Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe by March 2012.

Power:

A major challenge has been erratic power supplies in the country, where load shedding in-country is now occurring at more frequent rates and for prolonged periods in some cases for as long as 8 hours per day, every day.

ICT tools

Zimbabwe still enjoys duty free importation of ICT tools in order to increase the usage of these tools in country.

Policies

A national ICT policy is in place and efforts are being made to incorporate numerous sector wide policies including e-Health.

Despite all the challenges a number of e-Health applications are underway in country. These include:

- Strengthening of the national health information system through the use of the District Health Information System (DHIS). This system is deployed throughout the country and captures data from all the 67 districts in the country. Mobile application tools are supporting the system where mobile phones are being used in remote facilities reporting to the national database;

- Human resource information systems. Human Resources for Health are being tracked through an integrated database system that includes relevant regulatory authorities, and the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. This system can transfer data to the National Health Management Information System (HMIS), which is the DHIS. In addition, private sector systems and ordinary citizens can query the registration status of health practitioners with their respective councils.

- Private Sector Initiatives: A number of private sector initiatives are beginning to take hold with one service provider linking all care centers in a single network.

- Telemedicine applications: the medical school has installed a telemedicine application through which teaching and training can be provided to undergraduate medical practitioners.

- Knowledge repositories: the medical school has access to key international data repositories currently accessible to postgraduate and undergraduate health care practitioners.

MEDICAL DEVICE [including SaMD] REGULATION / REGISTRATION

[http://www.samed.org.za/dynamicdata/Events/ConferencePresentations/99.pdf]

Medical devices market in Zimbabwe is not regulated. The current situation in Zimbabwe is that the Authority only regulates condoms and gloves yet there is need for wider quality assurance for medical devices;

Medical Device Regulations Draft: [https://www.mcaz.co.zw/]. Not in force yet!

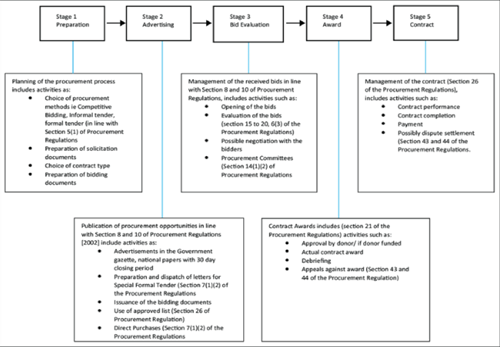

ZIMBABWE PUBLIC PROCUREMENT PROCESS

PROCUREMENT REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF ZIMBABWE [PRAZ] – (procedures, tips on tenders, review of tenders): http://www.praz.gov.zw/index.php?lang=en

Operational issues & challenges

10 THINGS STARTUPS NEED TO CONSIDER when developing Electronic Health Record (EHR) solutions in Zimbabwe:

- User experience - The design and workflow of the medical enterprise software shouldn’t unnecessarily contribute to the high workload that doctors already have. Writing clinical notes is already a tedious and mundane activity which is why doctors’ handwriting is witchcraft! Therefore EHRs should be designed to relieve that stress. The EHR should be able to capture relevant clinical information intuitively through features such as auto-transcript or voice dictation. Another solution is incorporating handwriting recognition features…

- Standard architecture - Standards are necessary for interoperability. We are yet to have e-Health standards enforced by legislature however there are established international standards of architecture that can be adopted. Recommended examples are the Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) and Continuity of Care Document (CCD) used in the US healthcare system…

- ICD-10 vocabulary - Another important standard necessary for interoperability is using the same health coding system for naming and classifying diseases…

- DHIS-2 compatibility - The benefit of electronic health information systems is their ability to track individual and population health problems and treatment over time. This enables us to timely identify and respond to disease outbreaks. The Ministry of Health adopted DHIS-2 as the national health information system for collection and analysis of routine health services data. To prevent data silos and blind spots arising in the private health sector it is important that all EHRs be able to contribute to the ministry’s DHIS-2 system.

- Clinical Decision Support Features - A game changer for the local EHR market would be an intuitive system that is able to assist doctors in their day-to-day clinical decision-making…

- Patient access - Patients have a right to access information about their own health and treatment at any time. EHR systems should have a patient portal in accordance with this right. It would be notable to go a step further and develop a Patient Health Record (PHR) that allows the patient to have a longitudinal track of their treatment.

- Mobile access - For convenience the EHR system should grant mobile access. The dictum “Think mobile first” abides here.

- Privacy and security - For ethical reasons privacy and security have to be at the heart of the EHR system development. Considerable investments have to be made towards securing the system…

- Customization of reports - EHRs should cater to the individual needs of the practice and be able to prepare unique reports. Game changers would be reports that can facilitate medical research through analyzing disease and treatment outcome trends.

- Medical Aid society tracking - There is an ongoing “war” between healthcare providers and healthcare fund managers in Zimbabwe. Doctors are really desperate for solutions that will enable them to electronically submit claims, check policy validity and reconcile amounts paid and owing.

FACTORS INFLUENCING e-HEALTH IMPLEMENTATION BY MEDICAL DOCTORS IN PUBLIC HOSPITALS IN ZIMBABWE:

Improving access to health care services in both developed and developing countries through information communication technology (ICT) has been getting particular attention from government, medical researchers and practitioners. This has seen many governments proposing the implementation of healthcare systems that are centered on technology, while researchers and practitioners have been arguing for policies that promote the use of technology in healthcare provision

In line with the above, a study was conducted to determine the factors influencing implementation of e-health by medical doctors in public hospitals in Zimbabwe

The study was guided by a qualitative research in conjunction with multiple-case studies.

This study revealed that the implementation of e-health by medical doctors in public hospitals in Zimbabwe is influenced by both internal and external factors. Internal factors include ICT infrastructure and e-health technologies, ICT skills and knowledge, technical support, security concerns, lack of basic medical facilities, demographic factors such as age and doctor-patient relationship. External factors are health policy, funding and bureaucracy.

The idea of e-health is relatively new to healthcare centers in Zimbabwe. Its application has not been sufficiently addressed. The study shows that the success of an e-health system depends on internal and external factors. There is a great potential for implementing e-health in Zimbabwe if these factors are taken into consideration…

Read more…http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1560-683X2018000100010

ZIMBABWE’s HOSPITAL REFERRAL SYSTEM: DOES IT WORK?

[https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-019-0369-1]

Case studies / Proof of concept

VULA MEDICAL REFERAL APP

VULA is the brainchild of Dr William Mapham, who conceived the idea for the app while working at the Vula Emehlo Eye Clinic in rural Swaziland. He experienced first-hand the difficulties faced by rural health workers when they need specialist advice.

William is an ophthalmologist. He has served as the Vice Chair of the Rural Doctors Association of South Africa (RuDASA) and previously spent time in New York and Washington designing mobile phone applications for healthcare. He has published academic articles on the role of innovation and technology in improving healthcare delivery, and has extensive experience in rural health care.

Working as an ophthalmologist in remote rural areas in the Eastern Cape, South Africa and Swaziland, Dr William Mapham had first-hand experience of what it was like to work as a healthcare worker without proper support and access to specialist care.

To combat the struggles of healthcare workers, Dr. William Mapham sought to bring about systemic change by bridging the gap between digital technology and healthcare.

One of the triggers for the idea was bumping into a patient after he worked in a rural hospital in the Eastern Cape, where he had written a referral to see a specialist in Umtata as he did not know how to treat him due to lack of expertise at that stage. Seven years later, he learned that the patient had lost vision in one eye, as he had never got to the specialist. Mapham knew that he had had access to the information at the time, the medication had been actually available in the clinic and he would have been able to save an eye.

Although it wasn't conceptualized right then — it was a fellowship at Columbia University in the United States of America that led the tech entrepreneur to see the potential for mobile app technology to attempt to solve Africa's historical access problems in the healthcare sector. Fast forward to 2014, the idea inspired the innovative, Vula Mobile — a diagnostics and referral app that links primary healthcare workers in remote areas with on-call medical and surgical specialists in South African hospitals in under 15 minutes.

A grant from the Shuttleworth Foundation, and some prototype design work from Flow Interactive (now part of Deloitte Digital) helped Dr Mapham to win the SAB Foundation Social Innovation Award in 2013. The prize money enabled him to launch the app for Android and iOS in July 2014.

The app was initially only for ophthalmology referrals, but it quickly became clear that the functionality provided by Vula was widely needed. Specialists from several different fields donated their time to work with the Vula team to design functionality for their own specialties. Vula added HIV, cardiology, orthopedics and burns in April 2016. This redesign enabled the app to scale to include referral forms for any number of specialties.

The aim of the app is to give health workers – particularly those in remote rural areas – a tool that helps to get patients quick and efficient specialist care.

The real-time, chat-based system streamlines the process of diagnosis by enabling healthcare professionals to capture and send pictures of the patient's condition to a specialist, who then delivers a diagnosis, prescribes treatments or schedules an appointment for surgery. This allows specialists to gain access to under-serviced areas, in a quicker and more efficient manner. To date, the multi-award winning m-Health app has served over 123,000 patients. In addition there are 7 200 registered health workers of which 1 200 are specialists and it has launched its 20th specialty. While the Cape Town-based startup has fostered a relationship with the Department of Health and has secured up R1 million in funding from HAVAÍC, it is also working on a new partnership-based commercial revenue model that seeks to raise $500,000 from companies in the private sector to assist 100,000 patients during the course of the year.

A few of the highlights of VULA in Zimbabwe describe how things have come a long way from the initial launch in July 2014.

Double the users…

The number of health workers registered on VULA more than doubled from 1,775 at the beginning of January 2017, to more than 3,600 a year later. There are now some maps compiled that show where the registered specialists are based and where the non-specialist users are.

Double the impact…

Impact is measured in terms of patients helped per quarter. 2.5 x increase from 2016 to 2017, from 2,397 patients helped in the fourth quarter of 2016, to 5,888 patients helped in the same quarter of 2017 and over 7,500 patients in the first quarter of 2018.

Major challenges for the expansion have been articulated in the question of “who is the health worker”, stressing validation as the biggest problem. For example, In South Africa, there is easy access to medical records, so it is easy to find out exactly who is a health worker, and only health workers are allowed onto VULA. In fact, the Company openly discourages the general public to download the app. The problem is at the app design-medical records “relationship” - how to make it country specific and role out to countries that don’t have that? In Zimbabwe for example, most of the health records are in a ‘room’ and it is not quite feasible to send someone to check every time someone tries to register, so the VULA design team is looking at ways to solve that and once that’s done, the expansion would be much easier.

Beyond the impact on individual patient care, VULA has been recognized as an experiential training tool. Primary health workers learn case by case how to manage conditions with specialist guidance. The University of Pretoria and the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Family Medicine Departments are also using VULA to monitor and train their medical and clinical associate students remotely.

WHO Relevant resource documents

References

http://www.stoptb.org/partners/partner_profile2.asp?PID=87525

http://siapsprogram.org/zimbabwe/

https://www.theunion.org/what-we-do/technical-assistance/tuberculosis-and-mdr-tb/tb-care

https://www.financialgazette.co.zw/zimbabwe-gets-set-for-telemedicine/

https://www.sundaymail.co.zw/e-health-takes-shape/amp

https://www.business1.com/medical-software-companies/zimbabwe

https://www.mcaz.co.zw/index.php/medical-devices

http://www.samed.org.za/dynamicdata/Events/ConferencePresentations/99.pdf

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/efc0/38d2c0fbf098631573672c365a3249050482.pdf